It was around Thanksgiving 26 years ago that Beverly Woodard learned she might soon be a mother.

But unlike most women, she didn’t discover the joyous news from a pregnancy test or a visit to her doctor. She got word in a call from a social worker.

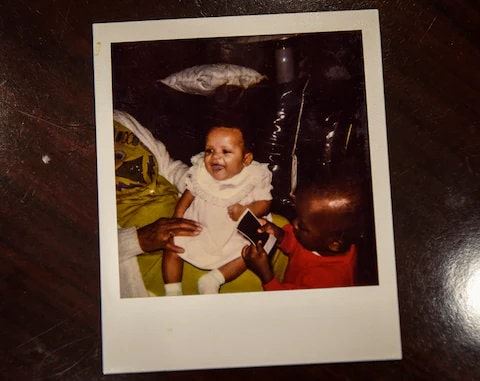

“ ‘I’ve got the baby for you,’ ” Woodard recalled the social worker telling her before Woodard received a Polaroid photo in the mail of a baby in a frilly dress.

Instantly, Woodard fell in love with the smiling, chubby-cheeked face and immediately knew that the girl in the photo was the baby she would adopt.

“I carried this picture every day” for months “and showed it to people and said, ‘This is going to be my daughter,’ ” Woodard said.

Adoption has always been important for Woodard — it’s what made her a mom. But the relationship Woodard has with her daughter Ashley feels even more special each November when the Prince George’s County judge finalizes adoptions in circuit court for National Adoption Day.

Woodard, 66, has presided over the county court’s Adoption Day festivities since 2010 and in November helped finalize the union of 10 new families. It’s one of the happiest events that takes place in a courthouse that regularly sees murder trials, child-custody battles, divorce proceedings, and acrimonious lawsuits.

“There’s no better feeling than Adoption Day,” Woodard said.

Woodard was a prosecutor handling child abuse and sex assault cases in the Prince George’s State’s Attorney’s Office around 1990 when she decided she wanted to adopt. She had a “wonderful career” at the time, she said, but there was a hole in her heart that she needed to fill.

She began researching legal adoption agencies and taking classes at Morgan State University every Saturday to earn her certification, despite skepticism from friends and family.

The Polaroid snapshot Beverly Woodard carried of the child who would become her daughter. (The Washington Post)

“ ‘You’re single. How can you do that?’ ” Woodard said of the questions. “ ‘You have a demanding career. You don’t know what the child’s history was.’ ”

Woodard knew she could overcome it all.

Soon after she finished her classes, Woodard got a call about a baby girl she would later name Ashley.

Ashley’s mother had left her at the hospital after giving birth. In a profile that Ashley’s biological mother wrote for the adoption process, she said she already had a 5-year-old and didn’t think she had the means or ability to raise a second child, Woodard said.

“She loved Ashley,” Woodard said. “She just didn’t think she could handle two children.”

Woodard met Ashley on a Wednesday and was told to come to pick her up on Friday.

The mother-to-be didn’t have a crib, know how to change a diaper, and had no idea how to stock her house for an infant. But in 1991, she picked up her daughter from the Department of Social Services in Baltimore and took Ashley, then 7 months old, home.

Like all parents, Woodard faced challenges.

With her family in New York and work giving her only five days to bond with her daughter, the newly single mother leaned heavily on the “village” around her.

A neighbor who ran a daycare agreed to tend to Ashley after Woodard returned to work. And a close friend answered Woodard’s questions — about everything from diapering babies to heating bottles.

Amid all that hard work, Woodard’s happy family has almost broken apart. Three years after Woodard brought Ashley home, a man who believed he was the child’s biological father emerged and wanted custody.

Maryland law requires adoptive parents to search for a child’s father based on information from the biological mother. The name Ashley’s birth mother gave led to a man imprisoned in New Jersey who said he would have his mother care for Ashley.

“I was so heartbroken,” Woodard said. “I was scared and didn’t know what was going to happen.”

But DNA tests soon revealed that the incarcerated man was not Ashley’s father. And a second man named as a possible biological father agreed to the adoption.

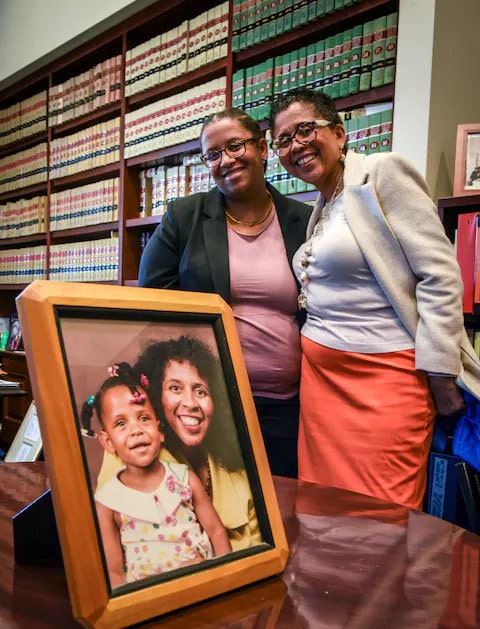

Judge Beverly Woodard, right, with her daughter, Ashley. (Bill O’Leary/The Washington Post)

On July 6, 1994, Woodard officially adopted Ashley.

Woodard told the story of her daughter’s adoption in her court chambers recently with Ashley, now 26, at her side. Woodard spread out a pile of photos featuring mother and daughter throughout the years while bags of blankets, toys, and gift cards for families welcoming adopted children lined the halls of her office.

“It never really loses its effect,” Ashley Woodard said of hearing the tale again. “It makes me feel really lucky not only to get adopted but to get adopted into this situation. I don’t think I could have picked a better parent.”

Ashley, who graduated from Towson State University with a degree in electronic media and film, tries to attend each National Adoption Day event in Prince George’s, which has finalized more than 50 adoptions this year. In years past, the court has seen a family adopt a baby abandoned in a dumpster at the University of Maryland and a disabled woman adopt a disabled child.

Ashley says she hasn’t felt any less love or different from any other child because she is adopted. She and her mother will dance around the house, binge-watch Netflix shows and go shopping together. And each night before bed, Woodard tells her daughter she loves her, to which Ashley always responds, “I love you too, lady.”